Something new today! Deviating from my series on fairy tales, I am posting this short essay on Soviet SF. This is a different corner of unreality to explore in my Guide to Unreality.

In Ivan Efremov’s groundbreaking SF novel The Andromeda Nebula (1957), there is a pivotal scene, jarring against the sunny background of the utopian society of the future. One of the characters named Mwen Mass (more about the names in the novel later) makes a tragic mistake in his scientific research which causes the deaths of several people. The future Communist society of the novel has no jails. But it does have a sort of penal colony called the Island of Forgetting where people who are unwilling or unable to participate in the bustling Great World of unified humanity are sent into exile or exile themselves voluntarily, as Mwen Mass does. Among these exiles are women who refuse to hand over their babies to the collective childrearing facilities. Mwen is shocked when he sees one of these women being threatened with rape, as sexual violence is unknown in the Great World. He realizes that what he sees is the “face of the beast” that had ruled humanity for millennia until the advent of Communism. This beast is selfishness, individualism, and cruelty born out of ignorance.

Two questions should be asked here. The first is whether a Communist utopia could survive without something like the Island of Forgetting where its rejects are dumped. The second is why wanting to bring up your own child is seen as a crime. It turns out the answers to these questions are connected

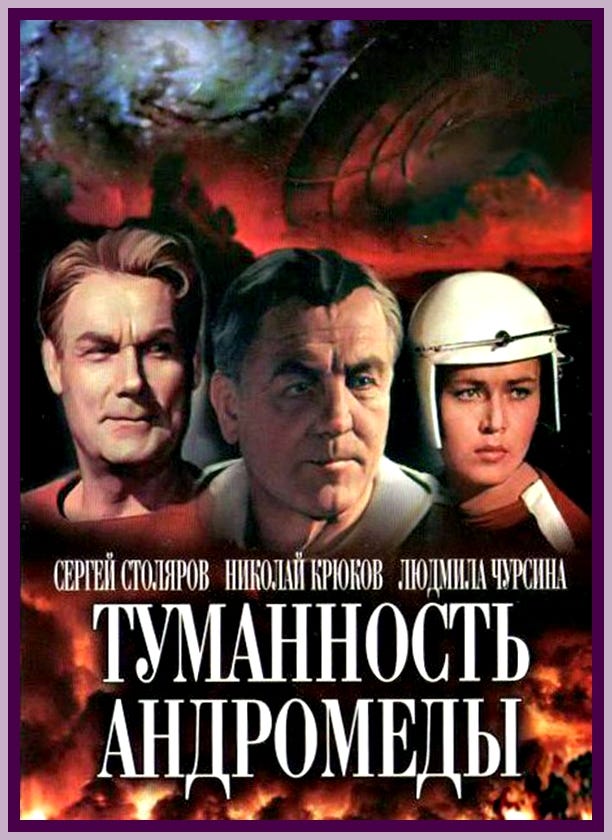

Ivan Efremov (1908-1972) was a towering figure in Soviet SF. A polymath, a famous geologist, and the author of many historical novels in addition to his SF writing, he was a fervent Communist. While the official line in the USSR had always been that socialism, the state’s ownership of the means of production, was the transitory stage toward full Communism, few writers before Efremov tried to represent the utopian society of the future. This is why the publication of the novel had "the effect of an explosion" (Revich 198). For the first time, the Soviet society crawling out of the horrific aftermath of the Great Patriotic War and Stalin’s Terror was shown a picture of what all the sacrifices had been for. And it is an incredibly attractive picture in many ways. In the Communist utopia, there is no racism, no misogyny, no economic inequality, no scarcity, and no violence (except on the Island of Forgetting). People are uniformly beautiful, strong, healthy, and creative. They are busy exploring

the universe, building new technologies, producing wonderful art, and establishing communication with humanoid aliens. What’s not to like?

The problem with the novel is that Efremov, totally sincere in his political commitment, inadvertently gives away the secret of utopia. It is not made for human beings - at least, not the human beings as we are today.

Let us go back to the issue of names. All the characters have made up names that sound very strange in Russian: Kart San, Per Lin, Erg Noor, etc. The reason is the deliberate erasure of ethnicity and race under Communism. Names that connect us to our national histories cannot be allowed in a society that sees itself as the negation of history. No one in the novel is Russian, American, or Chinese. No one is either white or non-white. All are the result of the massive manipulation of the human genome that blends together disparate population strands to create a New Man, a Communist Ubermensch. This eugenical intervention also removes undesirable traits, including hereditary diseases and even physical ugliness, from the gene pool.

Together with improving humanity’s stock, Communism also improves the ecosphere. The Earth is cleansed from the detritus of industrial capitalism and changed to suit humanity. The planet is brought to a state in which one can “walk barefoot” everywhere (261). No “green” reverence for the environment here: nonhuman and human nature are clay in the hands of utopians. Both the moral evil inside the human soul and the “evil” of dangerous predators and deadly viruses are eradicated by what Efremov calls, ominously, “liquidation teams”.

Now the importance of communal childrearing is clear. Efremov knows that manipulating heredity alone is not enough to break the stubborn heritage of human selfishness and cruelty. Nurture must join nature. There are no families in utopia, though there is a lot of romantic love and coupling. But the family, as per Marxism, is seen as a vehicle of oppression or worse, of replicating the structures of power that support the “monstrous despotism” of economic and gender inequality.

Rereading Efremov, I am struck by how sincere his utopian faith is, but also how astonishingly blind he is to the consequences of his own vision. The only way to change human nature is by violence. But violence cannot be contained on the Island of Forgetting. It will spread out until it consumes the entire society as did, in fact, happen to the USSR. And this violence was not the product of some sociopaths who took over and ruined the utopian enterprise. It was inherent in the nature of utopia itself.

Isaiah Berlin, a great liberal philosopher and historian, attributes the collapse of utopias to what he calls “the crooked timber of humanity”. Human nature is what it is. We are self-centered, individualistic, often cruel, but also capable of kindness, altruism and creativity. These two sides of humanity are inextricably linked because they are the product of human freedom. If you try to straighten this crooked timber, you will end up with a pile of debris.

To be fair to Efremov, he eventually becomes aware of this. In 1968 he wrote a sequel to The Andromeda Nebula called The Hour of the Bull, which is an even better novel. There he confronts Communism with a dystopian capitalist society on the planet symbolically named Tormance (torment). The ruler of Tormance asks a utopian superwoman: "How could it happen that the ravished, robbed planet turned into a marvelous garden, and its savage, faithless inhabitants-into loving friends?" (175). He receives no answer because there is none.

Works cited

Revich, Vsevolod. Perekrestok utopii (The Crossroads of Utopias). Moscow: Iv Ran, 1998

Efremov, Ivan. Chas byka (The Hour of the Bull). Moscow: MPI, 1988.

… Tumannost Andromedy (The Andromeda Nebula). Moscow: Molodaya gvardia,

1959.

That's fascinating that there's so little utopian fiction produced in the early decades of one of the most self-consciously utopian political projects in history. If nothing else, I would have thought the Stalin era would have seen someone trying to defend what was happening as historically necessary and inevitable (as H. G. Wells more or less did in The Shape of Things to Come).