If asked to name the first fairy tale that comes to mind, most people would probably say “Cinderella”. But it is actually uncharacteristic of the genre. If you remember the schematics of the fairy tale introduced in the first instalment, you will see how Cinderella barely fits the plot and character functions. First, as opposed to many tales in which the protagonist departs from home and faces dangers and obstacles, Cinderella, the most domestic of all heroines, barely stirs from her nook by the fireplace. Second, she does not battle or conquer the villain. Third, while she indeed achieves the happy ending by marrying the prince, how much of this success can be attributed to her actions? The passivity of Cinderella has been a constant cause of irritation for feminist writers, as I will discuss below. But in one way, at least, Cinderella does fit the Propp/Zipes format. She receives the magical gifts that bring her wealth, fortune, and happiness. The third plot function of Zipes’ scheme goes as follows:

“There is an encounter with: (a) a villain; (b) a mysterious individual or creature, who gives the protagonist gifts; (c) three different animals or creatures, who are helped by the protagonist and promise to repay him or her; or (d) three animals or creatures who offer gifts to help the protagonist, who is in trouble. The gifts are often magical agents, which bring about miraculous change.”

But what are the actual gifts Cinderella received? What did she do to earn them? And most importantly, who is the giver? Let us explore these questions. And the first step is to get rid of the whole fairy godmother-enchanted pumpkin-glass slipper storyline. This is not what Cinderella is all about.

The fairy godmother was introduced in Charles Perrault’s version of Cinderella titled “Cendrillon” and published in 1697. Perrault, writing for the mannered and affected French court, made his retellings of fairy tales appropriate for his audience consisting of adults pretending to be children, and rich and powerful pretending to be simple and humble. Half of his version of the story has to do with elaborate 18th-century fashion, as the sisters prepare for the ball:

“They were wonderfully busy in selecting the gowns, petticoats and hair dressing that would best become them. This was a new difficulty for Cinderella; for it was she who ironed her sisters’ linen and pleated their ruffles” (Hallett 101).

The tasks that other fairy tale protagonists have to undertake may be killing a dragon, or finding the immortal villain’s heart locked in an egg, or saving a kingdom. For Cinderella, it is pleating ruffles (though, to be fair, I would probably prefer killing a dragon myself). Perrault appends two “morals” to his story. The first one is directed at the little girls who read the story and identify with Cinderella in her beautiful gown with her handsome prince by her side:

Beauty is a fine thing in a woman; it will always be admired. But charm is beyond price and worth more, in the long run. When her godmother dressed Cinderella up and told her how to behave at the ball, she instructed her in charm. Lovely ladies, this gift is worth more than a fancy hairdo; to win a heart, to reach a happy ending, charm is the true gift of the fairies.

This is an instruction in passive, obedient, decorative femininity. The second moral, however, is even worse because it reveals how the ruffles and glass slippers of fairy tales for children is simply a cynical wink at his mature, world-weary aristocratic audience:

It is certainly a great advantage to be intelligent, brave, well-born, sensible and have other similar talents given only by heaven. But however great may be your God-given store, they will never help you get on in the world unless you have either a godfather or a godmother to put them to work for you (Hallett 102).

If we compare Perrault’s version with the Grimm Brothers’ “Ashputtel” we find no explicit moralizing. Instead, older and darker elements surface, especially in the description of the tasks Ashputtel has to accomplish in order to go to the ball and in the gruesome punishment meted out to the stepsisters, which is omitted in Perrault’s version and of which more later. The tasks are not ironing petticoats. The evil stepmother throws a dishful of peas into an ash-heap and tells the girl she needs to separate them in two hours. But if you are ready for Cinderella to do something besides suffering patiently, you will be disappointed. She does not get a sieve to filter the ashes. Instead, she pleads for help, and the help is given:

“The little maiden ran out the back door into the garden, and cried out:

Little tame pigeons,

Turtle-doves too,

If you don’t help me

What shall I do?

Come pick up the seeds

All the birds in the sky,

For I cannot do it

In time if I try” (Complete Grimm Brothers Tales, 91)

The birds do Cinderella’s bidding, and not just once but three times. But why? At least, Perrault gives an explanation of sorts: Cinderella has a godmother, as everybody would have in a Christian society where every baby was baptized, and this godmother happens to be a fairy. But in the Grimm Brothers’ tale, there is no indication that Cinderella has any magic of her own. How can she command birds of the sky?

And birds are not the only creatures to obey her. In the Russian story of Vasilisa the Beautiful which has some elements in common with Cinderella, the heroine is helped in her domestic chores by a little doll her dead mother had given her before she died. In still other versions, it is ants, bees and other insects that run to the rescue.

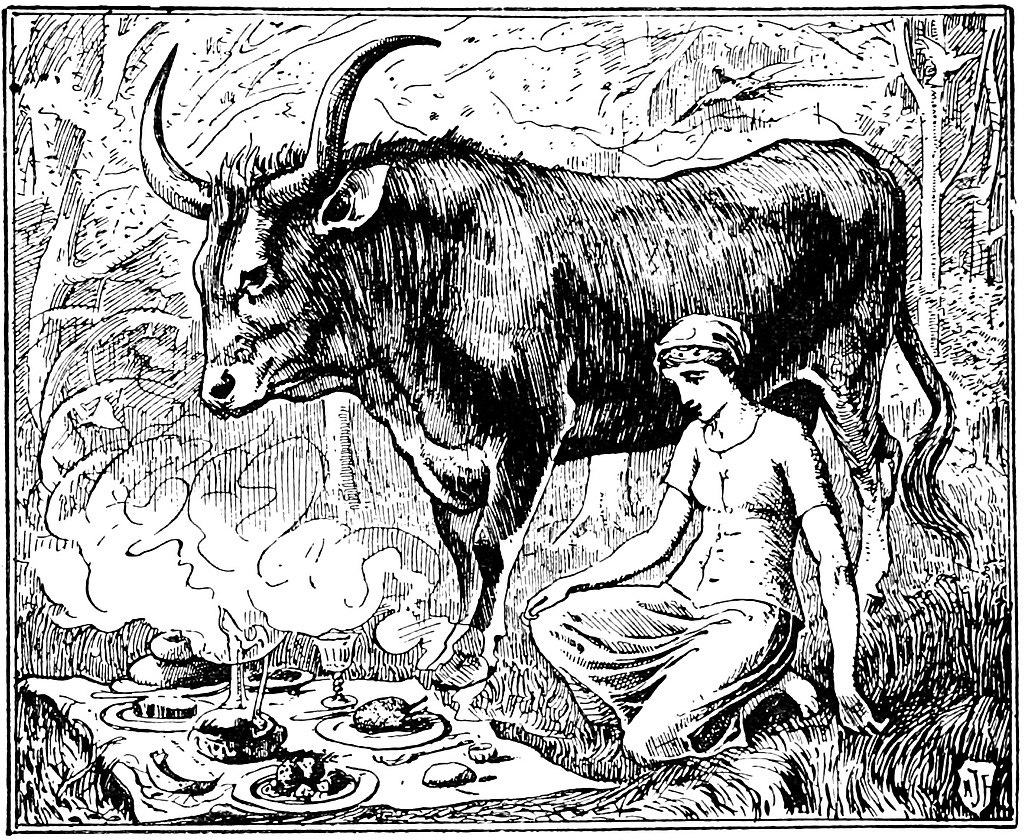

Not all avatars of Cinderella are as helpless as the archetypal character herself. Vasilisa is a prisoner of the horrible witchlike Baba Yaga and daringly escapes her clutches (in my novel Nightwood, I expand this story into a major part of the plot). In the Norwegian story of Katie Woodencloak, Katie, who is a princess-in-hiding, fights a three-headed troll with the help of her magic bull. But it is the Perrault’ version with its pretty, passive, and virtuous heroine that has captured the public’ imagination, inspired Disney, and caused a feminist backlash.

Feminists did not like Cinderella. Anne Sexton in her groundbreaking collection of poetry Transformations (1971) was scathing about “that story”:

Cinderella and the prince

Lived, they say, happily ever after

Like two dolls in a museum case

Never bothered by diapers or dust…

That story (Hallett 138).

Sara Maitland in “The Wicked Stepmother’s Lament” (1987) presents an upside-down story of Cinderella in which the stepmother is trying to protect the girl by teaching her how dangerous, violent, and misogynistic the world is, and how one needs to be able to fight to achieve one’s goals. But Cinderella is just too naïve and full of misguided belief in human goodness to learn the lesson:

“She would not look out for herself. She was so sweet and so hopeful; so full of faith, and forgiveness, and love. You have to touch anger somewhere, rage even; you have to spit and roar and bite and scream and know it before you can be safe. And she never would” (Hallett 131).

Tanith Lee, a wonderful fantasy writer, published a classic collection of feminist rewritings of fairy tales called Red as Blood, or Tales from the Sisters Grimmer in 1983. In her version of Cinderella, the beautiful girl named Ashella is in fact a witch, a servant of Satan, bound to his will by her dead mother. And while she goes to the ball and meets the prince who promptly falls in love with her beauty, her goal is not marriage and happily ever after. She wants to avenge her mother who killed herself when she was exposed as a witch and was in danger of being arrested. When the clock strikes twelve, Death enters the ballroom, and the prince is driven mad by the sight of a glass shoe.

Lee undoubtedly thought of her story as a daringly modern feminist challenge to the laws of patriarchy deeply entrenched in traditional fairy tales. But a closer look at the history of Cinderella reveals something surprising. Lee’s provocative is, in fact, closer to the ancient originals than Perrault’s coy version.

The one common motif in all the older versions of Cinderella is that of the dead mother. Not just in the sense that Cinderella is mistreated by her stepmother whom her father marries after her mother passes away, but in a more startling way. The magic gifts Cinderella receives, the ones that enable her to triumph over her enemies and reach the happy ending, are given to her by her mother’s ghost.

In “Ashputtel”, the heroine plants a hazel twig on her mother’s grave, waters it with her tears, and as the hazel tree grows out of the grave, a bird comes to sit on the tree and eventually gifts her with progressively more beautiful dresses and the tiny glittering shoes that fit only her. In pagan religions of Europe, hazel is a witch-plant, while birds are messengers of the dead.

In the Russian tale of Vasilisa the Beautiful, the gift from the dead mother is a magic doll that has to be fed in order to help Vasilisa with her tasks. Dolls are widely used in magic rituals (voodoo dolls) and in secret pagan ceremonies.

In other versions, Cinderella is helped not just by birds but by animals like the bull (“Katie Woodencloak”) or the ewe (The Sharp Grey Sheep”). But these animals are dead. In order to become the magic helpers to the Ash-Girl, the animals have to be sacrificed. The bull tells Katie to cut off his head, flay him, and hide the skin under the rock from which the gifts will be coming.

Many religions have some version of a story about the hero descending into the underworld to receive magic powers from the chthonic deities ruling the dead. Gilgamesh and Enkidu; Odysseus conjuring up spirits of dead heroes of the Trojan war to help him find his way back home; Orpheus pleading with Hades to release his dead wife Eurydice; and of course, Christ descending into Hell after his death on the cross to redeem the souls languishing there. And there is a female version of this descent into the underworld in the Greek myth of Demeter searching for her daughter Persephone in Hades’ dark kingdom. That myth was so important for ancient Greeks that it became the foundation of the Elysian Mysteries, a secretive but powerful cult.

So, is it possible that Cinderella, with her ruffles and glass slippers, is in fact one of those mythic heroes and heroines who defy death to receive supernatural powers? Could it be that when the clock strikes twelve, she flies back to her kingdom of ashes and bones – the underworld, the kingdom of the dead? Could it be, in fact, that Cinderella herself is a ghost?

The punishment imposed upon the evil stepsisters in “Ashputtel” is horrifying. They have parts of their feet amputated to fit into the shoe. They are exposed as impostors when the prince notices blood sloshing out. This graphic moment is in keeping with other cruel and unusual punishments in fairy tales, like the one meted out to the evil stepmother in Snow White, which we will talk about next time. But we also know that blood sacrifice is used to raise the dead, as Odysseus does to the shade of Achilles. What if the blood of the stepsisters is what gives flesh and substance to the ghost of the Ash-girl – the ghost who flies away at the stroke of midnight? What is the pretty maiden who commands birds, insects and dead animals, is in fact the goddess of the underworld herself, an avatar of Hekate or Hel, the Nordic giantess whose name is a cognomen of Hell? What is Cinderella and her dead mother are one and the same?

The feminist anger with the Disneyfied image of feminine passivity and obedience is understandable. But perhaps it is misplaced. Perhaps we should look deeper into Cinderella’s story and find an unsettling image of the ancient female power that communes with the dead and commands the living. Call her Ashella, or Ashputtel, or Cinderella – she is the girl of bones and ashes, and when she comes to your ball, don’t be surprised if the bells tolls for the funeral rather than the wedding.

If you take Cinderella all the way to Hell, it might be worth mentioning Innana/Ishtar's descent into the underworld, where clothes (and jewelry, and makeup) also play a central role

Inana - https://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/section1/tr141.htm

Ishtar - https://sacred-texts.com/ane/ishtar.htm