There has been a lot of discussions in my feed recently about utopia. People seem to have taken umbrage at my claim that utopia necessarily leads to totalitarianism. Well, I stand by this claim. But I also suspect that some of the problem is terminological. People mean different things by utopia. So, here I am to clear (some of) this confusion.

Let us start with utopia. The term utopia was coined by Sir Thomas More in his 1516 book of the same title, describing a fictional island society. The word comes from Greek: οὐ ("not") and τόπος ("place") and means "no-place“. However, it can also mean “a good place” (eutopia). A utopia, therefore, is the blueprint for an ideal society.

More’s utopia has some troubling features, such as slavery (slaves are convicted criminals). On the other hand, it embraces what we today call equity: there is no economic inequality, no accumulation of riches, no ostentatious consumption, and even children are distributed equally, so as to create uniform family size. Subsequent utopias follow the same drive for perfection, even though their ideas of what perfection is, may differ,

(Here is a little video, summarizing the main aspects of More’s ideal society).

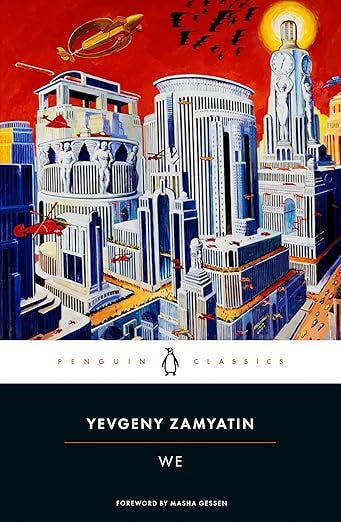

Utopias were written throughout the Renaissance and early modernity, but let’s jump to the late 19th and early 2o-th century. Suddenly, the literary world exploded with utopias and anti-utopias. On the utopian side, you had Vril, the Power of the Coming Race (1871) by Edward Bulwer-Lytton, Looking Backward (1888) by Edward Bellamy, News from Nowhere (1892) by William Morris, A Modern Utopia (1905) by H. G. Wells and many more. On the anti-utopian side, you had We (1924) by Evgeniy Zamyatin, Brave New World (1932) by Aldous Huxley and eventually the greatest of them all, Nineteen eighty-four (1948) by George Orwell.

Note that I said “anti-utopia”, not “dystopia”. And there is a reason for that. A dystopia is an extrapolation of some negative trends in contemporary society into the future. Dystopias are easy to write (which is why they are a favorite genre of YA). Climate change? In a dystopia, we are all floating on the rising seas or cooking in the overheated world. Greedy corporations? In a dystopia, we are cogs in a ruthless corporate machine. And so on.

But anti-utopias are a rejection of utopia as an ideology. That is to say, they take the blueprint for an ideal society and show why it would inevitably become hell. Krishan Kumar, one of the greatest scholars of literary utopias, writes in his groundbreaking book Utopia and Anti-Utopia in Modern Times (1987), that anti-utopia is predicated “on the very terms of modern utopia” (Kumar 110). He also writes: “Anti-utopia is, in essence, a relatively recent invention, a reaction largely to the socialist utopia of the nineteenth century and the socialist practices of the twentieth century” (Kumar viii).

The reference to socialism shows what anti-utopias are all about. Socialism and communism (the two are not the same but it is another subject) were the greatest utopian ideologies of modernity. A utopian ideology is the political project of creating an ideal society. What literary utopias described, utopian ideologies tried to create. We all know the results. But as Kumar points out, anti-utopias were written precisely by people, like Zamyatin and Orwell, who originally embraced some variety of socialism, only to become profoundly disillusioned.

Squint at We and Nineteen eighty-four and you will see utopian features -equality, uniformity, purity, communal living - but reflected through the lens of reality. Human nature is not infinitely malleable, as Winston Smith tries to prove to his torturer in Orwell’s novel. At some point, people will want more than their neighbors have. Or maybe they will want different things: an unattainable partner; luxuries that are in excess of what is “rational”; a private room where one can do whatever one wants. It is not an accident that in We and Nineteen eight-four, the collapse of the system starts when the protagonist falls in love - or lust. Desire cannot coexist with social perfection.

But what about alternative utopias or heterotopias? These started to proliferate in the 1960s and 1970s with the rise of counter-culture. The most famous ones are probably Ursula Le Guin’s The Dispossessed (1974) and Samuel Delany’s Triton: An Ambiguous Heterotopia (1976). Both are written at the time when the failure of socialism is becoming clear. Both writers are trying to escape the straitjacket of a utopian ideology and to present an alternative to the status quo which does not rest on the embrace of static perfection. In other words, they want to reconcile utopia and history.

Of the two, Le Guin’s book is better known and to my mind, less interesting. It is almost an allegory of the dissident movement in the USSR, with Shevek, her protagonist, doing what so many Soviet scientists did - escaping to the West. As opposed to him, though, none of them went back trying to reform the calcifying system which, they knew, was beyond salvation.

Delany’s novel is wry, ironic, and unsettling. Its subtitle of “heterotopia” is often confused with Michel Foucault’s use of the same term in his essay “Of Other Spaces”. But Foucault’s heterotopia is something else entirely (too be discussed in another essay). Delany seems to mean a society that accommodates difference and diversity in a way in which traditional socialist utopia did not. But the novel shows that while such a post-scarcity society may be possible, it will not deliver the main promise of utopia: universal happiness. You may not have accumulation of wealth but you will still have inequality based on social capital. You may not have exclusion based on race or gender, but you will still have exclusion based on group dynamics. And even when all desires are satisfied, people will still want more.

The protagonist of the novel named Bron, much like the heroes of Orwell and Zamyatin, falls in love with an unattainable woman. The Spike is a successful artist in a society where success is measured in recognition, not money (something that we can understand very well in the age of social media). She has no interest in Bron. And so, he decides to do something about it. If he cannot have his ideal woman, he will become her. In this future, sex change is easy and commonplace. So, Bron undergoes the complete rewiring of his body and mind, becoming a heterosexual woman. But when she meets the Spike, Bron still wants to be loved, admired and respected by her, and the Spike still does not care. The novel ends with Bron agonizing over this slippery desire that can never be tamed, never satisfied, always asking for more than any utopia can give, as she realizes that “sure will never come”.

So, are utopias relegated to the same dustbin of history where socialism had initially relegated capitalism? In the next essay, I will discuss the concept of “utopian impulse” introduced by critics such as Fredric Jameson and Tom Moylan to salvage something out of utopia’s ruins. Until then, let us enjoy the imperfections of the present rather than dreaming of the perfect future that will never come.

Great essay. I haven’t seen the term anti-utopia used. It’s a useful distinction.

Ernst Bloch saw utopia as the human propensity for… hope. The “trauma” (my word) of fascism and Stalinism created an anti-utopianism where hope is something… delusional.

Should we send hope to the “dustbin of history”?

(Very interesting essay. Thank you. I’m not disagreeing with you, just adding some layer to what you wrote. Maybe you can address it in your next essay?)