Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings (LOTR) is a favorite among the fringe ultra-right and neo-Nazi groups. This fact is periodically brought up to revive an old debate: is fantasy inherently fascist?

This debate has been raging for over a thirty years. In his famous 1991 essay “The Politics (if Any) of Fantasy”, Brian Atteberry recounts an anecdote from his experience teaching in Italy:

“I was giving my usual heated defense of fantasy as an art form when I was interrupted by a comment from the students. ‘Here in Italy,’ they said, ‘fantasy is something that comes from the far right, and science fiction from the left’” 1

Giorgia Meloni, the current Italian prime minister from a right-wing party, is apparently a huge fan of LOTR, confirming Atteberry’s experience.

Other scholars have been pretty hard on fantasy too. In his seminal book Metamorphoses of Science Fiction (1979), which I talked about already, Darko Suvin calls fantasy a “reactionary” genre. He argues that, as opposed to SF, fantasy cannot generate cognitive estrangement because its secondary worlds are ruled by magic, not science. For him, SF is a Marxist genre; fantasy is a fascist (or at best, a conservative) one. And to go back to LOTR, some critics outright accused Tolkien of racism by pointing out that all Elves are white-skinned and all Orcs are dark.2

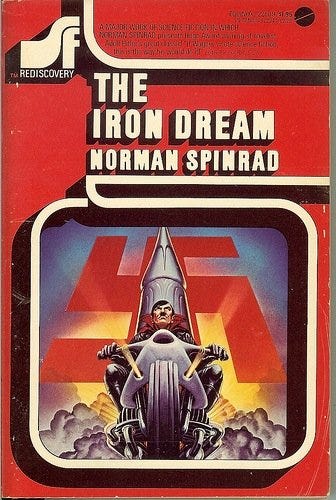

The most provocative exploration of the nexus between fantasy and fascism is a fantasy novel. Norman Spinrad’s astonishing The Iron Dream (1972) is metafiction: literature that comments upon its own status as literature; and in this case, a fantasy novel that ponders why fantasy and fascism are twins. Though I urge people to read the novel in full, here is a summary:

The bulk of the text is a story-within-a-story, titled The Lord of the Swastika, which is a fantasy novel written by Adolf Hitler who, in the alternative history of this secondary world, immigrated to the US in 1919 and became a hack writer rather than a Reichsfuhrer. The novel is a "sword and sorcery" yarn about the rise of a superhero named Feric Jagger cleansing his enchanted kingdom from pestilential monsters and evil Dominators. The Lord of the Swastika is framed by the scholarly Introduction written by the fictional academic Homer Whipple, of which more later.

The cleverness of Spinrad’s metafiction lies in the fact (unfortunately lost on some of his American audience) that The Lord of the Swastika is simultaneously a standard fantasy, employing all the clichés of the genre, and a very accurate depiction of the Nazis’ rise to power. Most characters are thinly veiled versions of Nazi politicians: not just Hitler-Jagger but also Goering, Goebbels and Hess. Indeed, if you consider how a ragtag bunch of losers led by a failed painter became the ruling party of Germany and plunged the world into an apocalyptic war, you may want to dismiss it as a fantasy, except that, unfortunately, it is the historical truth.

But the most unnerving aspect of The Lord of the Swastika is that it shows the close parallels between the standard tropes of fantasy and Nazi ideology. The evil Dominators are obviously the Jews, and the mutant monsters are the racial mongrels that the Nuremberg laws were supposed to defend against. But if you did not know that the author of this fantasy was Adolf Hitler, would you grasp this? Or would you just enjoy the ride?

The Introduction by the fictional Whipple sketches the alternative history of the world without the National Socialist German Workers' Party (the official name of the Nazis). World War 2 did not happen; instead the USSR just took over Europe. The Holocaust did happen, only it was perpetrated by the communists instead of the Nazis (considering that it was Stalin’s plan to deport all Soviet Jews, this is not far-fetched). And while Hitler-the-fantasy-writer is dead when the Introduction is supposedly written, The Lord of the Swastika has a cult-like following of fans who embrace its symbolism, aesthetics, and ideology. Much like the LOTR fandom, you might say.

The novel poses a whole lot of interesting questions. Was Hitler necessary for the catastrophes of the last century to occur? Had he not come to power or been assassinated, would history have taken a better turn? The book suggests that it would not have, debunking the “great man” theory of history. But alternative history or uchronia is the topic for a different essay. Here I want to go back to the intersection of fantasy and fascism.

How can a literary genre have a political ideology? This was the question asked by Fredric Jameson who in The Political Unconscious (1981), suggested a distinction between ideology of the form and ideology of the content. To simplify his somewhat abstruse argument, he claimed that each individual work reflects the views of its author, but the genre to which this work belongs reflects its history. In other words, Tolkien was certainly not a fascist, let alone a Nazi (the two are not synonyms). But epic fantasy, the genre he inherited from his 19th-century predecessors, such as William Morris and developed in a new direction, was born in the same political cauldron of modernity as fascism, and shared some of its basic assumptions. Among these assumptions is the idea of race as the engine of history; nostalgia for a simpler and more “natural” way of being in the past; obsession with the Middle Ages; and glorification of physical violence.

The problem with Jameson’s argument is that it ties a genre too closely to its history. But history does not stand still; and genres develop, mutate and evolve far faster than biological species. Fantasy today, even epic fantasy, is not the same as in the 1950s days of LOTR.

So, I suggest reversing Jameson’s scheme. Fantasy is not fascist; but fascism is fantasy.

Not in the pejorative way, “oh, it’s just a delusion”. No, fascism is quite real. But like any political ideology, it tells a story. And where you have a story, you also have a genre. The story that fascism tells is the story of intrepid heroes fighting subhuman Orcs and evil Dominators. It is the story of the glorified past that never existed - with castles and swords but without plagues and famines. It is the story of return to the roots and finding one’s true identity in the bewildering world of globalism and technology. It is a fantasy story.

Consider this excerpt from an educational tract published by the SS headquarters:

Just as night rises up against the day, just as light and darkness are eternal enemies, so the greatest enemy of world dominating man is the sub-man. This creature which looks as though biologically it were of absolutely the same kind, endowed by nature with hands, feet and a sort of brain, with eyes and mouth, is nevertheless a totally different, a fearful creature. It is only an attempt at a human being, with a quasi-human face, yet in mind and spirit lower than any animal.3

The important thing to understand is that it is not some overheated and hateful rhetoric. No, this is the literal description of the world in which the SS lived. They truly and sincerely believed that Jews were not human beings - or at least, some of them did. Walter Buch, the supreme judge of the Nazi party, wrote in 1938 that "National Socialist has recognized [that] the Jew is not a human being”. 4 A world populated by quasi-human monsters, plunged into darkness and purified by the forces of light - what is it but the generic world of fantasy?

Paul Verhoeven’s 1997 movie Starship Troopers was panned by some historically illiterate viewers who saw it as glorification of fascism. But just like The Iron Dream, it is an anatomy of fascism, a clever metafictional parody that lays bare its internal narrative. Ideologies are not a set of unrelated agendas or dry policy points. Ideologies are stories. They create overarching and all-consuming narratives of right and wrong, good and evil, past and future. Probe a fascist, a communist, and a woke activist, and you will find that their stories have consumed their entire being. They do not live in the same world that most of us inhabit. Their fantasies have become their realities.

So, to answer the question that periodically pops up in various forums: is fantasy fascist? No, but fascism is fantasy, a pernicious one, to be sure, but not the only one that can create an alternative reality in which you think you are killing Orcs when in fact you are killing Jews. In a future essay, I will discuss SF and its connection with Marxism and utopian socialism. Meanwhile, read LOTR - or maybe not. There are better fantasies out there.

Atteberry, Brian. Strategies of Fantasy. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1992.

Noel, Ruth. The Mythology of Middle Earth. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1978.

Abanes, Richard. American Militias: Rebellion, Racism and Rage. Downers Grove: Inter

Varsity Press, 1996.

Goldhagen, Daniel Jonah. Hitler 's Willing Executioners: Ordinary Germans and The Holocaust. New York: Vintage Books, 1997

“ I will discuss SF and its connection with Marxism and utopian socialism.” You could also look at fantasy utopian Marxism with the ideaology in the works of Ursula Le Guin. Perhaps over simplification of the left and right causes the argument to fall over, after all the left has only been around 200 years. It’s possible for anyone to romanticise and fantasise of utopias regardless of genre.

It’s an interesting premise. Fascism as I understand the term was a specific historic movement curated by Mussolini as a reaction to Communism. In the modern epoch, the word has become a handy, albeit easy, trope to denote some broad application of oppressive rule.

Myself, I exercise restraint in uttering terms like “fascist” and “dictator,” as dark impulses and tendencies and worst-case scenarios swim below the surface of every individual’s psychic pool. (Dostoevsky, as you know, wrote about this without parallel.)

These arguments come along every epoch or so and have an irresistible allure. My suspicion is that our interpretation of works by Tolkien and others exist independently of their creators’ artistic intentions. Perhaps they speak more to the biases and psychological DNA, as it were, of the reader rather than those of the artist. (Unless you’re someone like a George Lucas, who very consciously — and conscientiously — modeled his whole fantasy-scape after Joseph Campbell. I tend to not love that mode of contrivance.)