A frequent convention in SF is of aliens disguised as human beings and living among us. Everybody knows Jack Finney’s classic The Invasion of Body Snatchers (1953) and the endless movies based on it. Or consider Robert Heinlein’s Puppet Masters (1951), or on a gentler side, Kris Neville’s Bettyann (1970).

But how does it feel to be an alien in a human body, having to pass and yet acutely aware of your difference from the people who surround you, including your friends and neighbors? The SF novel mentioned above seldom address this question. But if you want to know, just ask me. I am that alien.

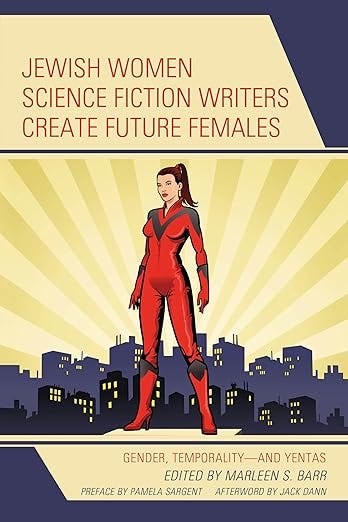

Last year, I was approached by one of my academic idols: Marleen S. Barr. She wrote one of the first academic books on women in SF, Feminist Fabulation (1992), which I regularly assigned in my courses and seminars. No surprise that I was thrilled when she asked me to contribute to her forthcoming book on Jewish women writers of SF. I was beyond thrilled to hold this volume in my hands and to read what Dr. Barr generously wrote about me in her Introduction, calling me “Israel’s premier science fiction scholar and science fiction writer.” Incidentally, the volume also contains a scholarly discussion of one of my stories “Sea of Salt” by Danielle Gurevitch, so I appear there twice: as a contributor and as a subject, which is the first for me. You can find the book here.

But what does it have to do with aliens disguised as humans? Well, my own contribution is an autobiographical essay, which explains why, to me, being a Jew and being an SF fan are synonymous. I am sharing parts of this essay with my subscribers today:

Until I was about twelve, I did not know I was Jewish.

How is this possible, you ask? Didn’t your family keep kosher? Didn’t you celebrate the High Holy Days? Most American Jews can go back to the memories of the schul, or bar-mitzva, or some other form of religious observance to shore up their identity. But here is one of the many ways in which I part ways with my American Jewish friends. My family were not just secular; they were atheists and communists, living in the country in which atheism and communism were the official creed. In the USSR, as in the Kingdom of Heaven, there was neither Jew nor Gentile.

At least, this was the theory. The practice was altogether different. Soviet Jews were the target of a particularly insidious and nasty form of antisemitism, in which “Zionism”, never quite defined, became an obscene label attached to every Jewish success. The official propaganda machine churned out volumes of “anti-Zionist” trash, recycling every antisemitic cliché, from well-poisoning (the infamous Doctors’ Plot) to treason. Few took this propaganda seriously in the waning years of the Soviet utopia, but it was as inescapable as a bad odor. Jews were not slaughtered or expelled but they were daily humiliated, made the butt of off-color jokes, whispered comments, and routine discrimination.

And so, when I, with my blue eyes and a Ukrainian family name, finally had to confront the fact that I was a Jew, it created a real crisis of identity. It is noble to suffer for what you believe in. It is understandable to suffer for who you are. But to suffer for nothing? For a blank target painted on your forehead by some unseen and malicious enemy?

Once I moved to Israel with my mother, I believed this crisis to be over. After all, the Jewish state is supposed to give you a sense of belonging. But of course, it is not as simple as that. Setting aside the fact that “anti-Zionism” did not disappear when its state sponsor melted away in the fires of perestroika, Israel is a country, not an identity. Even as its citizen, you have to define what it means to be Jewish.

And then I realized that I already had an answer. I had had it for as long as I remembered myself. Since learning to read at a very early age, I devoured science fiction and fantasy. I read and reread every volume of Jules Verne and H. G. Wells I could lay my hands on. I scribbled ideas for my future stories and novels. Even when I had to read James Joyce and Virginia Woolf for my degrees in English, my heart was with SF; with aliens, misfits, and wanderers; in other words, with people (or creatures) like me. Being an SF writer and being a Jew are, for me, synonymous.

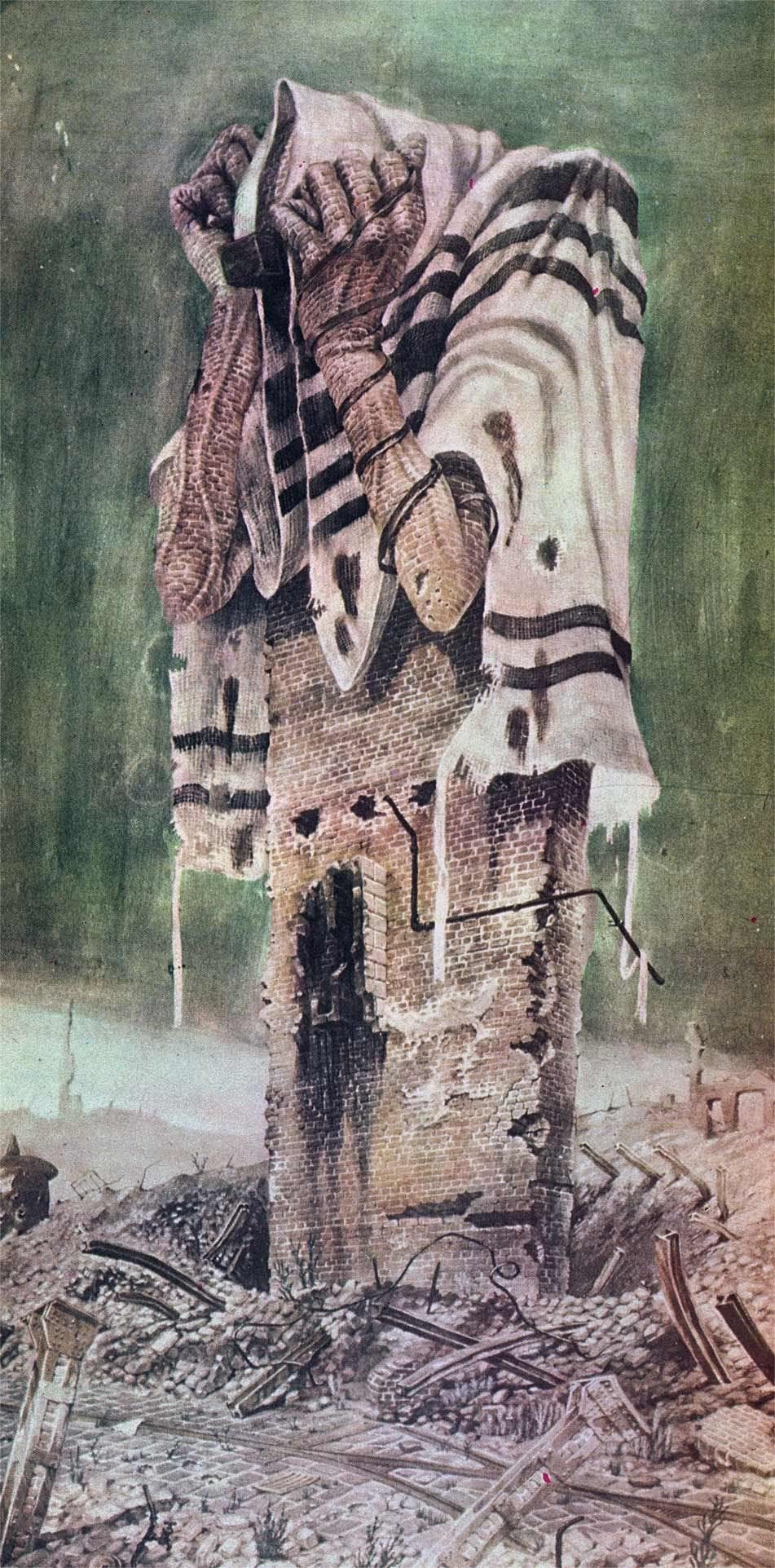

Of course, not all Jews are SF writers and not all SF writers are Jews (though many are). But something connects the alienation of being a Jew with the genre’s preoccupation with aliens. Jews are wanderers, restless nomads, belonging nowhere and everywhere. We are always out of place, and yet there are few places where Jews have never been. Our continuing existence is a mystery. Our success is a marvel. Our persecution is a horror.

In the Hebrew edition of Totem and Taboo, Freud describes himself as one “who is completely estranged from the religion of his fathers – as well as any other religion – and [one] who cannot take a share in nationalistic ideals, but who has yet never repudiated his people, who feels that he is in his essential nature a Jew”. Being Jewish means belonging through alienation.

My personal role model is Stanislaw Lem, a great SF writer and Holocaust survivor who dedicated his life to understanding the limits of humanity. Lem’s unparalleled portrayal of aliens in his novels such as Solaris and Fiasco owes everything to his experience in Nazi-occupied Poland when he passed off as a Gentile, a stranger in his own country, wearing a mask that was so like his real face. A secular and assimilated Jew, Lem, like Freud, never disavowed his Jewishness, though he could define it as little as the scientists in Solaris could define the mystery of the alien Ocean.

I have one advantage over Lem, though. I am a woman. Women, the archetypal Others of Western culture, have a special sensitivity to what lies outside the artificially imposed boundaries of the Same. As a science fiction writer, I am proud of standing with those who are different, strange, alien, and persecuted for being such. I am proud of being a woman – and a Jew.

I really enjoyed reading this! It is very well written. Thank you for sharing it with your subscribers. I am definitely going to check out those books. Congratulations on being published twice in Jewish Fiction Science Fiction Writers Create!

I also felt like an alien growing up, not because I'm Jewish (I went to Jewish schools and didn't socialise with significant numbers of non-Jews until university), but because I'm autistic and wasn't diagnosed until I was thirty-seven. Until then, I just thought I was weird, intellectually clever, but lacking in common sense, social skills and the ability (and, at times, the desire) to pass as "normal." I was bullied quite a bit for this.

Inevitably, this led me on to stories about aliens and time-travellers, other beings trying to pass as normal, but struggling, like me. I always empathised more with the aliens and eccentric scientists in these stories than with the "normal" viewpoint characters.

I think science fiction inevitably attracts outsiders and misfits, often highly intelligent ones, even before taking into account that science fiction has sometimes been stigmatised as a genre and required a willingness to pay a price socially to be caught reading it or talking about it in public. I have been laughed at in public on a number of occasions for my tastes.