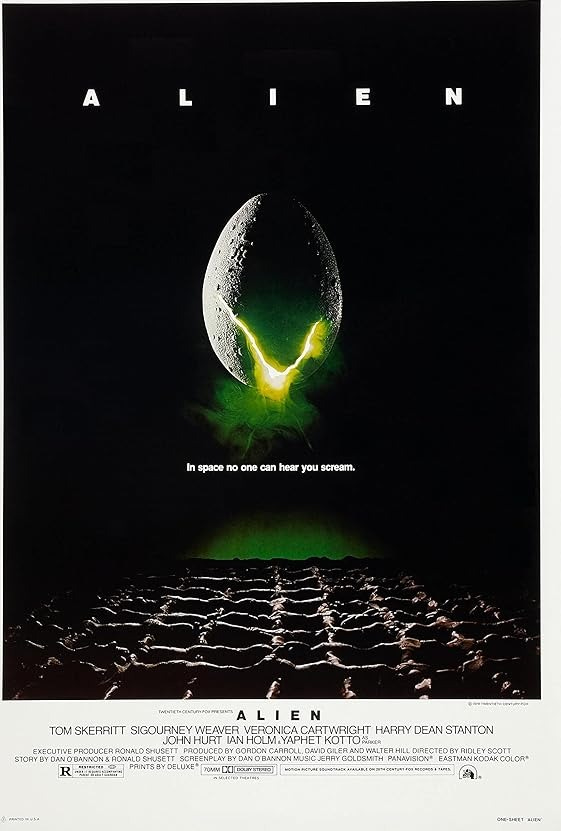

The first Alien movie was released in 1979. The same year, Darko Suvin published his groundbreaking book Metamorphoses of Science Fiction, which revolutionized the study of the genre. Suvin’s definition of SF has been tweaked, improved on, or modified but never surpassed. I will quote it in full and then unpack its somewhat dense academic prose:

Science fiction is "a literary genre whose necessary and sufficient conditions are the presence and interaction of estrangement and cognition, and whose main formal device is an imaginative framework alternative to the author's empirical environment."

What it means is that the purpose of SF is to make you change your perspective and look at familiar things from a different point of view (estrangement). And it does so by appealing to your intellect and encouraging the reader to think critically about their own reality (cognition).

In terms of Suvin’s definition, the first Alien movie is a perfect example of SF, despite its horror ambience. With its stunningly innovative design by H. R. Giger and its unusual portrayal of sex and gender roles (of which more below), the movie fulfils the first requirement of Suvin: estrangement. And it has also provided ample material for debates and disagreements, many continuing till this day; thus cognition.

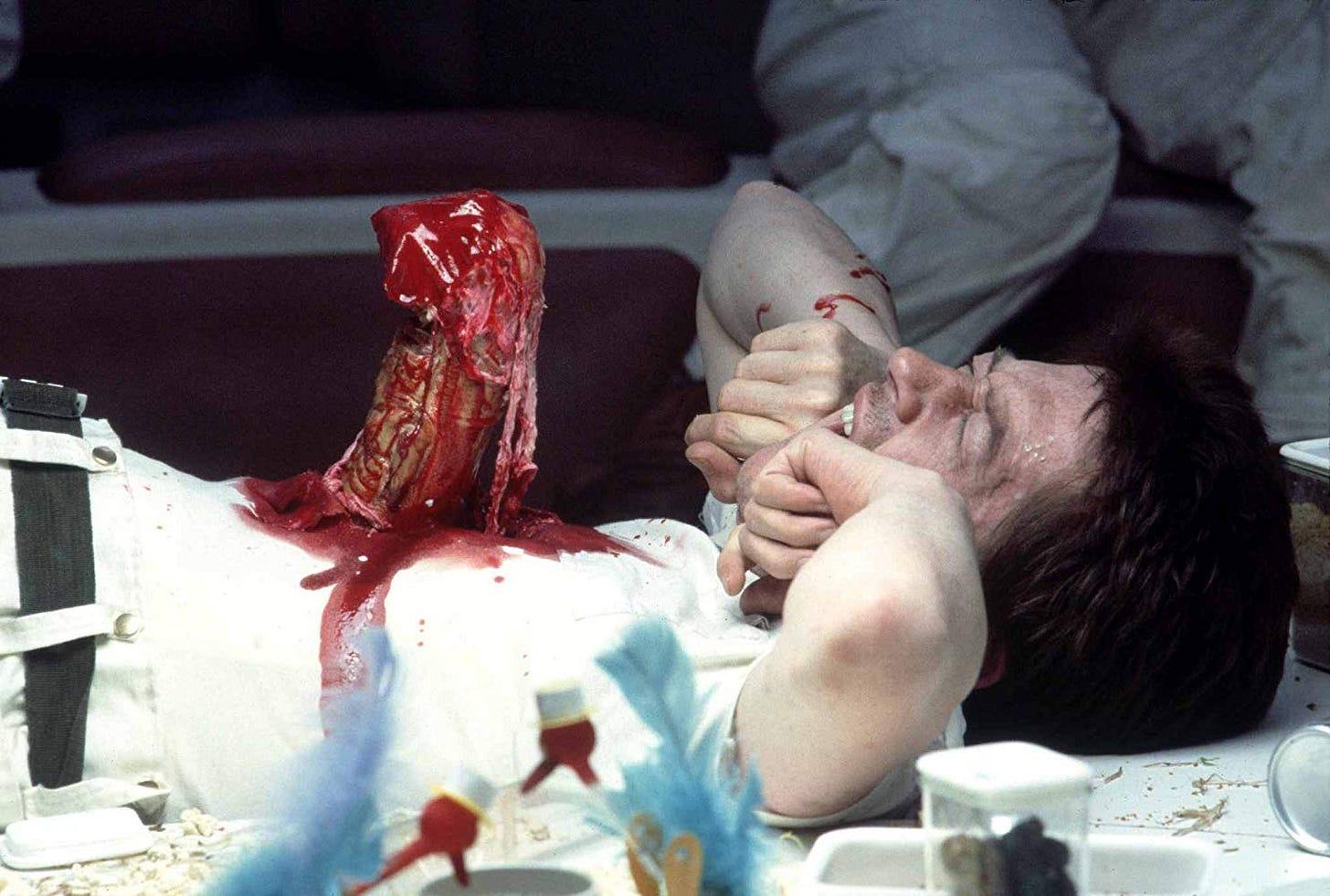

Probably the most iconic scene in the first Alien movie is the bloody emergence of the baby xenomorph from Kane’s body cavity, killing him in the process. It does not take much imagination to understand why this scene is so disturbing. It is a scene of birth transposed onto a male character.

In the sugary Hollywood iconography of smiling mothers cuddling cute (and carefully washed) newborns, we forget just how bloody, ugly, and painful the process of giving birth is. And it can easily kill you. In the 19th century, maternal mortality rate for England and Wales was 470 per 100,000 births (it is around 22 per 100,000 in developed countries today). 1 Read some Victorian novels and mark how many women die in childbirth and how matter-of-fact the attitude of their families is. Childbirth in human females is terrifying; and it is only modern medicine that shields us from its terror (unless you happen to live in a developing country where maternal mortality is still pretty high ).

The Kane scene played in my mind when I was pregnant with my first baby. Though I am happy to say my Caesarean was nowhere as dramatic as the movie, I felt the message of Alien in my own flesh. And the message is that the biology of sexual reproduction is uncaring, cruel, and bloody. A fetus, no matter how wanted, is a parasite in its mother’s body. But we are so accustomed to this reality that we do not see it for what it is. This is where estrangement (also called defamiliarization) comes in. Alien make the familiar reality of pregnancy and childbirth unfamiliar by transposing it onto a male body and making the fetus into an actual alien parasite.

But what about cognition? Alien forces us to consider not only the nature of biological reproduction but also the relationship between biological sex and socio-cultural gender. And it shows us that there is none. It fact, it questions the existence of gender altogether.

The protagonist of the movie and the only survivor is a woman, Ellen Ripley (whose first name is not mentioned until the sequels). She is tougher than any of her male counterparts; and though her femaleness is very obvious in the nudity scenes, there is nothing feminine about her. In fact, the role was written in such a way that it could have been played by either a male or female actor.

The revolutionary depiction of gender in Alien has been repeatedly noted by scholars and critics. As recently as 2019, critic Summer Reardon writes:

The portrayal of Ellen Ripley in the science fiction movie Aliens (Cameron) was a watershed in the filmmaking industry because it reflected the cultural changes brought about by an increasing number of women entering the workforce. The fact that the lead action hero of Aliens was cast as a woman is remarkable in itself, and is a reflection of the fact that the movie was released in a time period when women were increasingly working in nontraditional occupations…. Ripley’s depiction in Aliens therefore represents an important shift in film and media when it comes to women, and assumes greater importance than usual because of the impact it had on breaking through gender-based action genre conventions. 2

To follow Ripley’s trajectory from Alien to Aliens to Alien-3 is to follow the progressive decoupling of biological sex from social gender. Ripley is a female; but she displays none of the traditional stereotypical behaviors attached to her sex. Even when she assumes the protective role toward the little girl in Aliens, she does it by battling a monstrous image of maternity in the Xenomorph Queen. Ripley has a sex but no gender. And even more remarkably, neither does anybody else in the first three movies of the franchise. Kane who dies in childbirth like a Victorian heroine; the marines of Aliens who fight and die together, male and female alike; Ash who seems to be an incarnation of toxic masculinity but is revealed as a sexless android; all of them undermine our traditional notions of gender or sex roles.

But while gender is irrelevant, biology is central to the franchise. Xenomorphs incarnate the unthinking, predatory, pitiless nature of evolution. Their reproductive strategy - laying eggs in the flesh of other creatures and having its larvae parasitize on the host - parallels the reproductive strategy of parasitoid wasps whose larvae eat the paralyzed host alive. The horror of this made Darwin recoil from his own faith in a benevolent Creator. Darwin wrote in a private letter:

“I cannot persuade myself that a beneficent & omnipotent God would have designedly created the Ichneumonidæ [parasitic wasps] with the express intention of their feeding within the living bodies of caterpillars…”3

The reason why biological sex exists is to enable reproduction and perpetuation of the species. This is all. Gender or sex roles or any of the cultural baggage we have attached to this brute fact is irrelevant.

Alien is not the only SF depicting a world without gender but with biological sex. Other examples include Anne Leckie’s Ancillary Justice (2013) and Ada Palmer’s Too Like the Lightning (2017). Going back in time, Samuel Delany’s Triton (1976) and John Varley’s The Persistence of Vision (1978) depict a society in which sex change is so easy that nobody thinks of it as anything other than a cosmetic procedure. In Joanna Russ The Female Man (1972), an all-female society displays the entire range of gender roles we associate with both masculinity and femininity.

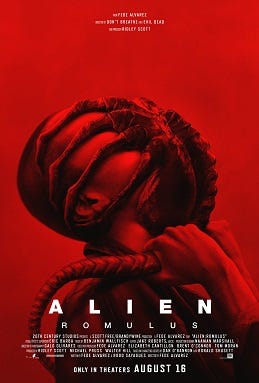

Alien was a revolutionary SF (and I suspect we still have not learned its lessons). But Hollywood just can’t leave well alone. The Alien franchise is a money-maker. A debate about sex and gender, on the other hand, is a straight road to cancelation and social-media pile-up. So, now we have Alien: Romulus, which is like Alien without estrangement, cognition, or any kind of intellectual content. It is so bland that you literally cannot say anything about it except that it is boring and derivative. One peculiar moment, though, is that the xenomorph-birthing scene has been given back to a female character. Does it mean we are going to have an informed discussion about the biology of reproduction and gender roles? Don’t count on it.

Darko Suvin, Metamorphoses of Science Fiction: On the Poetics and History of a Literary Genre (Peter Lang 2016; first published in 1979).

https://victorianweb.org/science/maternity/uvic/8.html

file:///C:/Users/egome/Downloads/Monsters_Marines_and_Feminism_in_the_198.pdf

Latter to Asa Gray, 1860. https://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/letter?docId=letters/DCP-LETT-2814.xml

I am gutted, emotionally. Xenomorphs and fetuses both drain the host. My now-adult son was always called “guest of my grand hotel” and I looked forward to his check-out date/eviction. We have regressed. A mother alien has lessons to impart that should terrify humanity and impart terror. There’s also the oral very sexual assault of the facehugger form. The other inversion that made men fear xenomorphs and think twice how women felt and experienced

As a mother, I can say there’s nothing feminine about giving birth. It’s as cruel as a war. Inside, every human creature is both a man and a woman and many factors determine the revealing of one or the other side.